Hände und was sie bedeuten

Im Zuge der Diskussion über KI und der Befürchtung, KI könnte die Kontrolle über den Menschen gewinnen, lohnt es sich, auch die anderen kognitiven Kapazitäten des Menschen zu betrachten. Es wird leicht übersehen, dass unser Gehirn – dem wir mit KI Konkurrenz machen – nicht das einzige wichtige Element des menschlichen Körpers ist. Die Hand geht dem Denken voraus. Nur dank der Hand ist der Mensch Homo Faber – ein technisches Wesen (Hans Blumenberg).

Von Beginn an ist der Mensch auf seine Hände angewiesen. Wir können nur selbstständig essen, wenn wir greifen, nur Raum erfahren, wenn wir tasten. Wir sind auf Berührung angewiesen und wollen berühren. Die mit ihrer Hilfe gemachten sinnlichen Erfahrungen benötigen wir zum Leben wie die Luft zum Atmen.

Sollte KI einmal das Denken übernehmen, werden wir auch weiterhin mit Hilfe der Hände überleben. Die Funktionen des Gehirns mag der Computer nachvollziehen können, die Hand steht außerhalb seines Wirkungsbereichs. «Während die Giganten der Tech-Branche von einer Eroberung des Universums träumen, soll etwas so Elementares wie eine menschliche Hand durch ebenjene neue künstliche Intelligenz nicht dargestellt werden können?» (Hito Steyerl).

Tatsächlich haben KI-Bildgeneratoren ein Problem mit menschlichen Händen. Aber auch wenn sie eines Tages soweit sind, sie richtig darzustellen, können Sie die Hand ersetzen? Es scheint nicht möglich zu sein. Denn anders als das statische Gehirn, sind Hände in Bewegung und auch wenn sich die reinen Funktionen technisch umsetzen lassen, das Nicht-Funktionale der Hände bleibt dem Menschen vorbehalten: Die heilende oder helfende Hand, die ausgestreckte, rettende Hand. Die Hand kann Vertrauen und Sicherheit geben – Verträge werden noch immer mit einem Handschlag geschlossen. Sie kann aber auch Gewalt anwenden und töten. Im Laufe des Lebens entwickelt und formt sich die Hand und steht für ein gelebtes Leben – Vergangenheit und Zukunft lassen sich in ihr lesen.

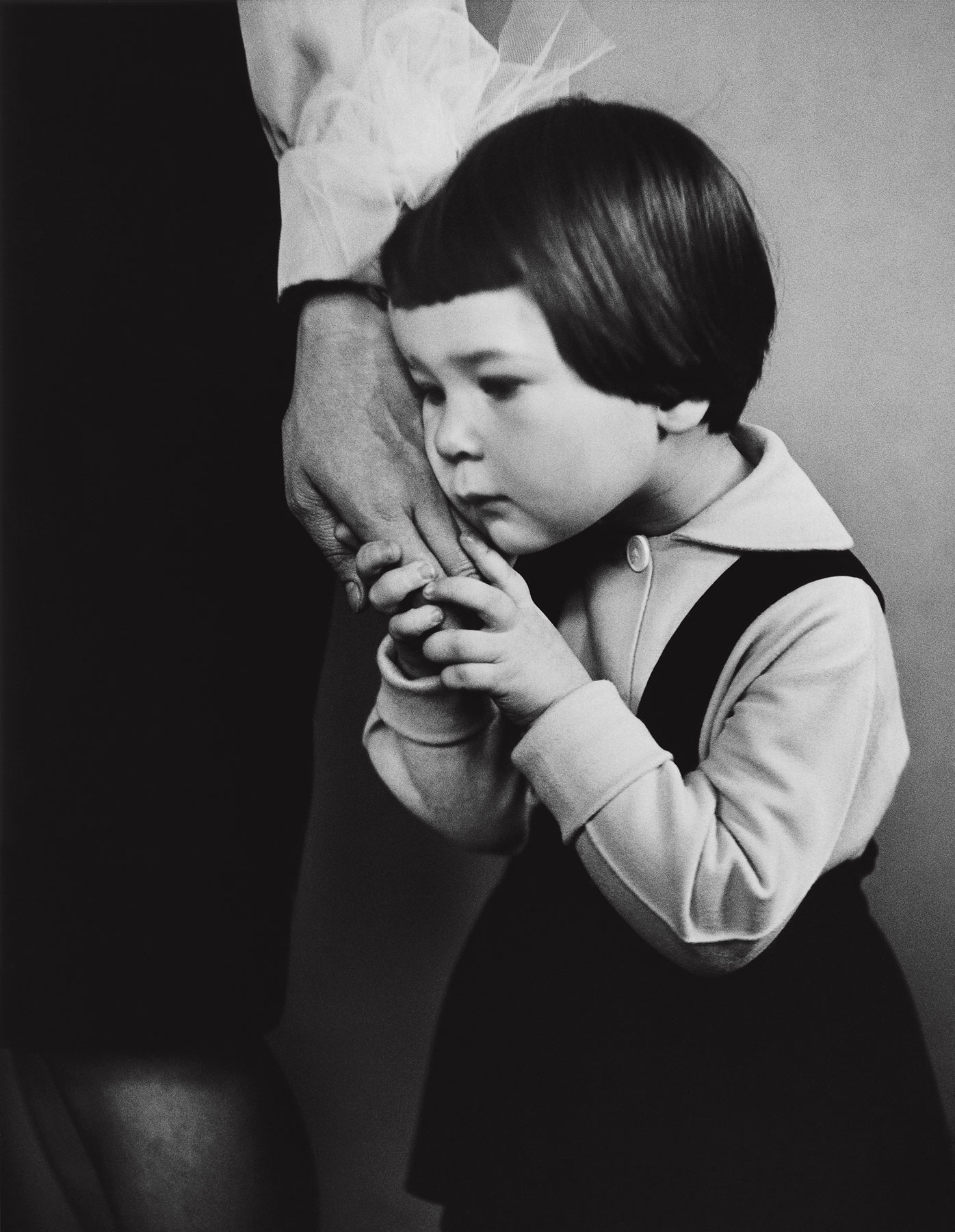

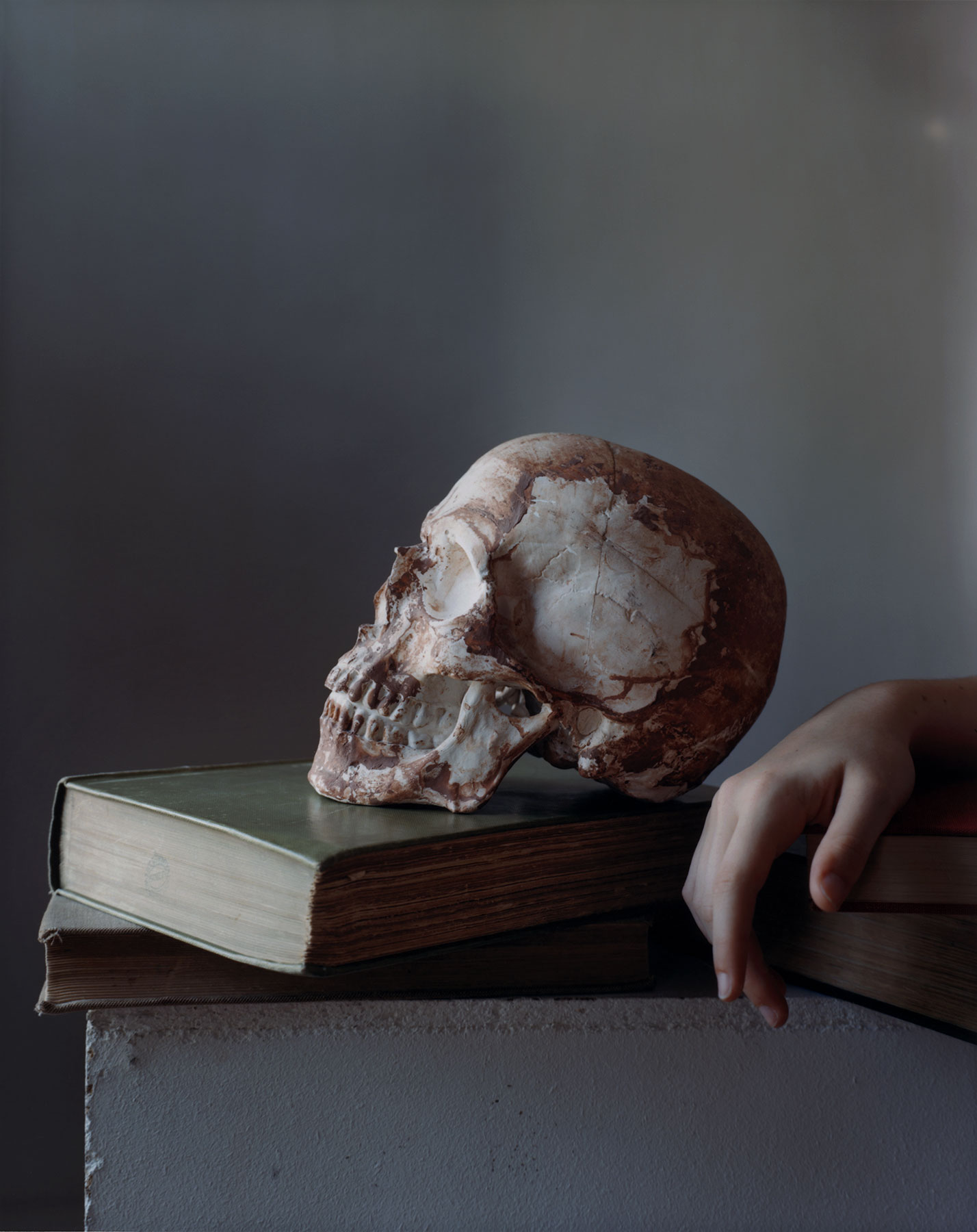

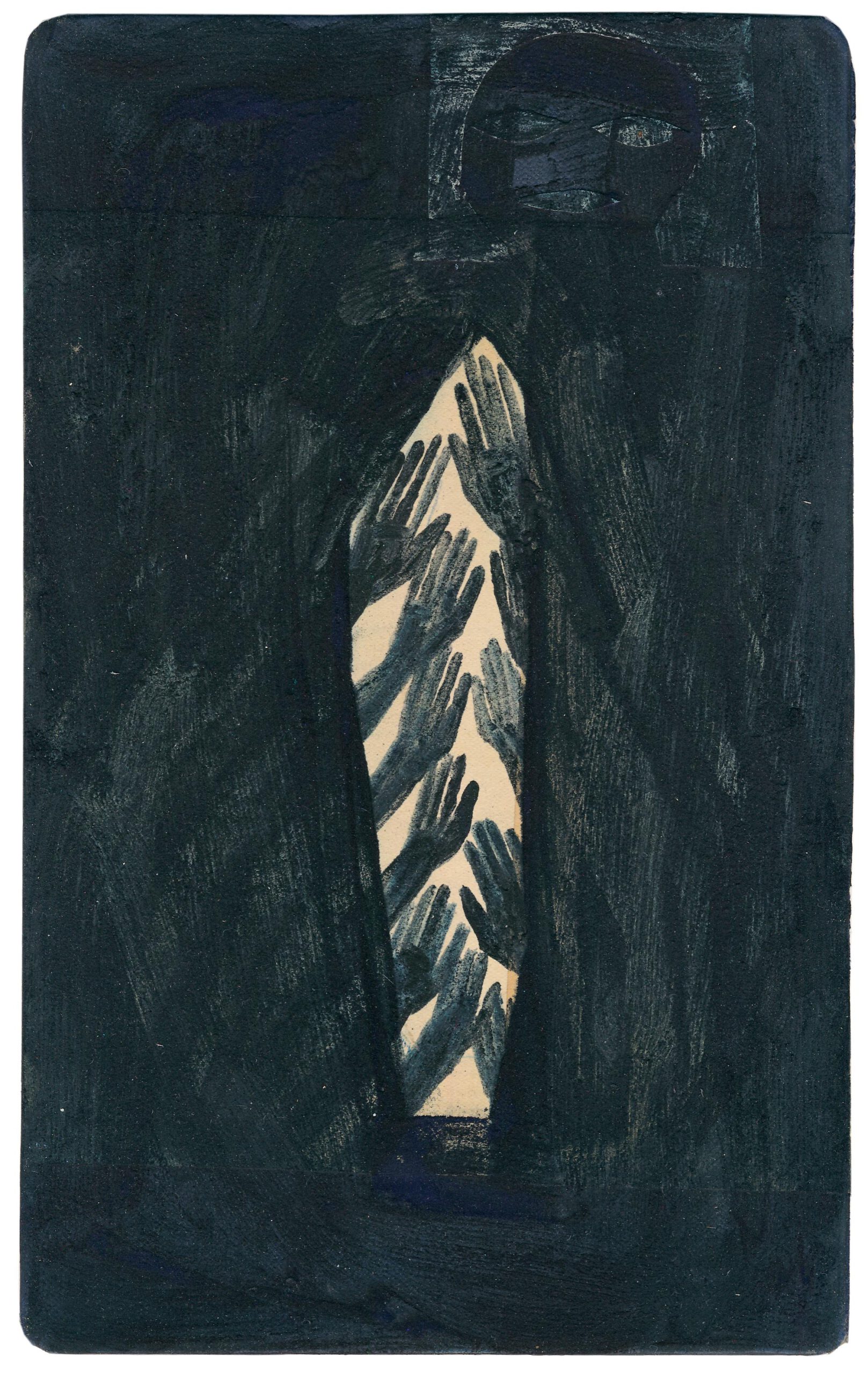

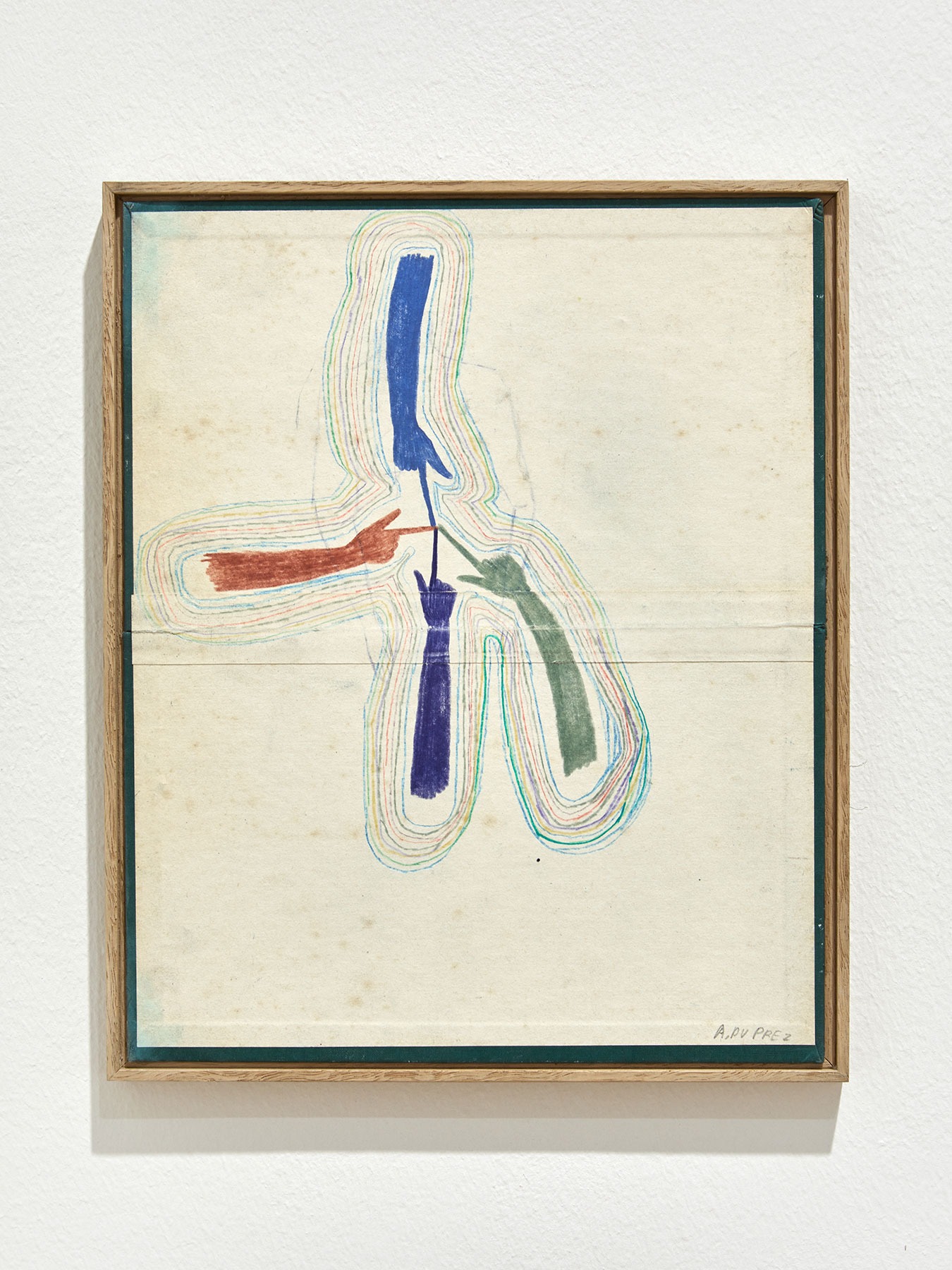

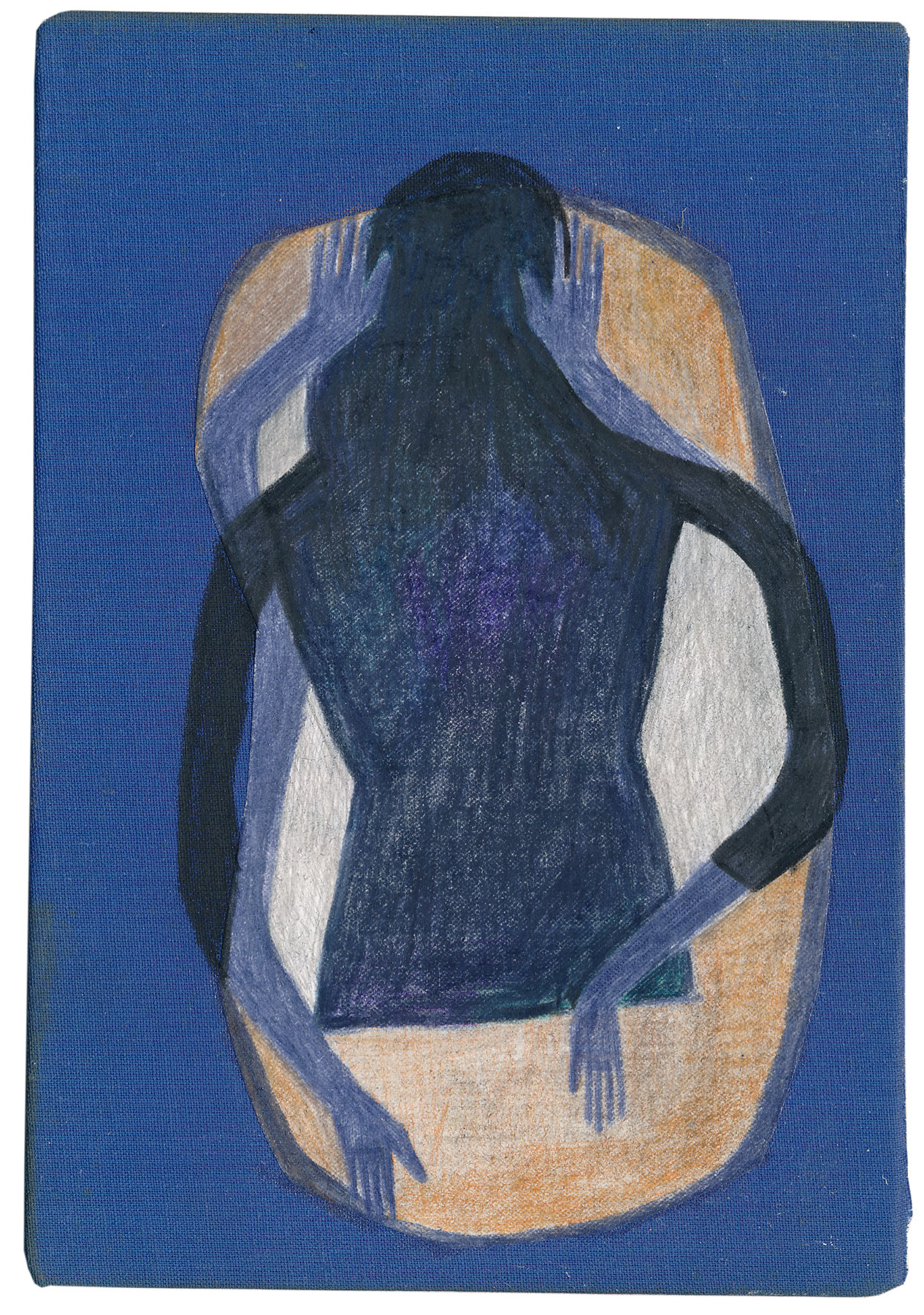

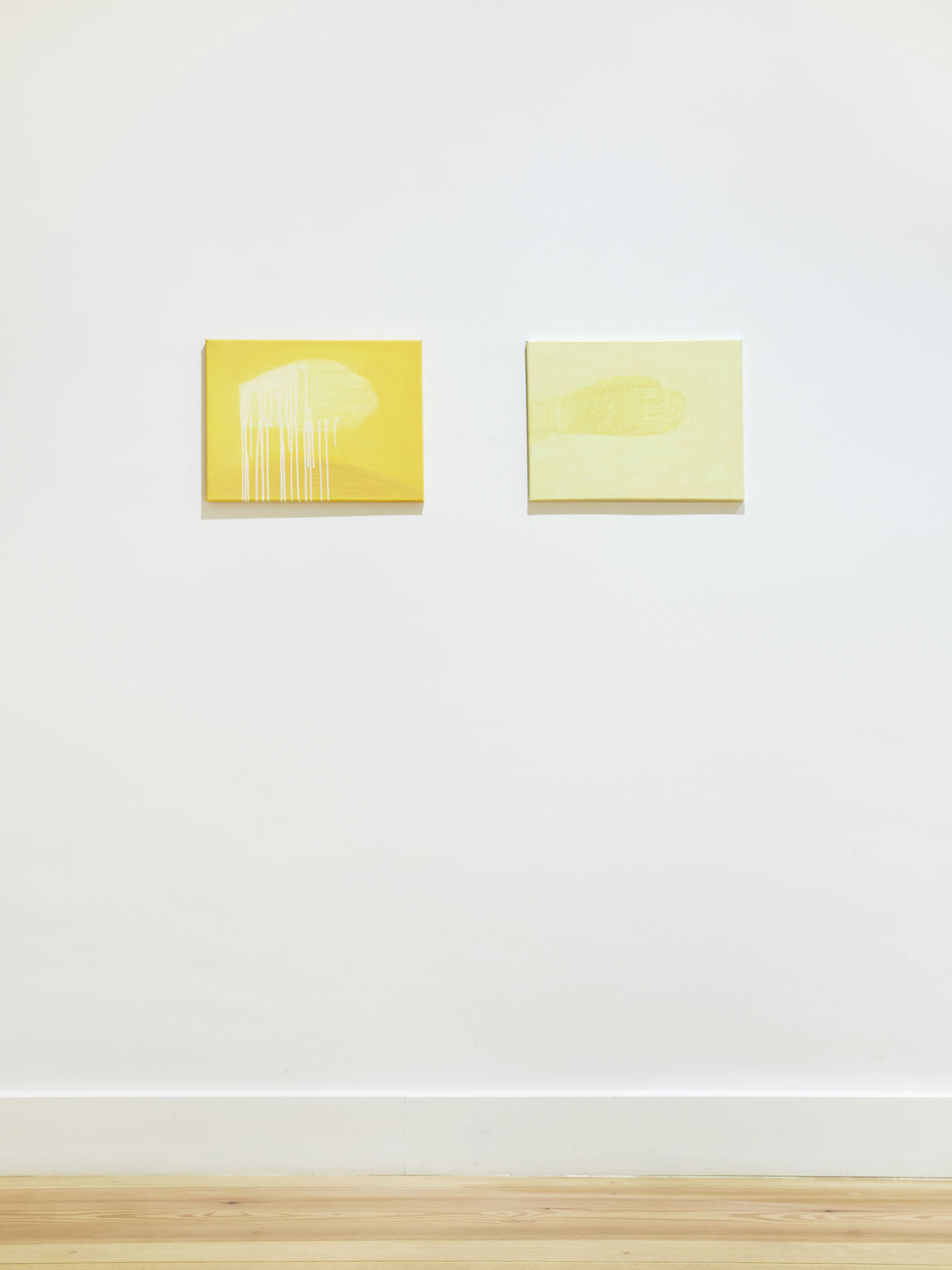

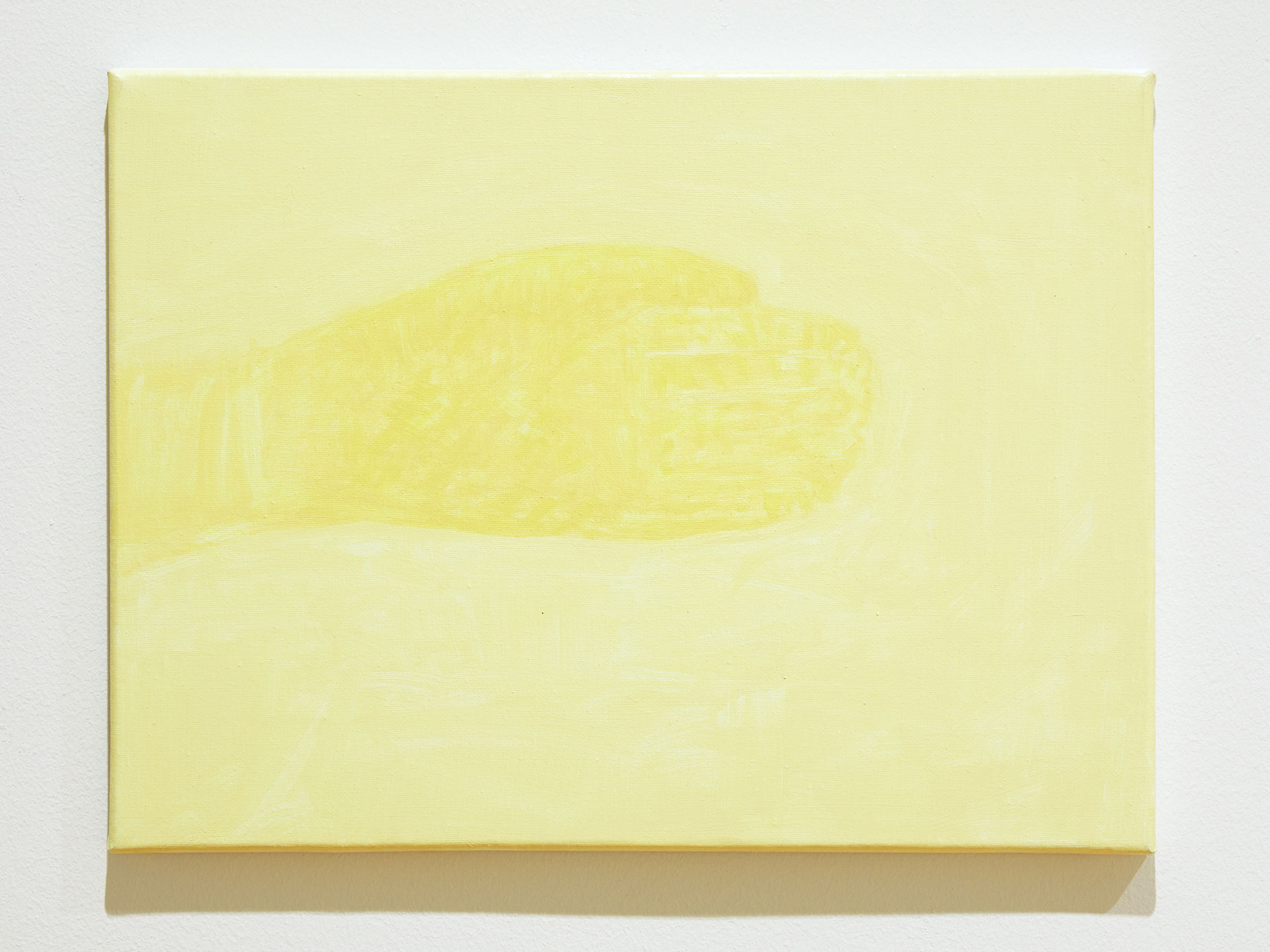

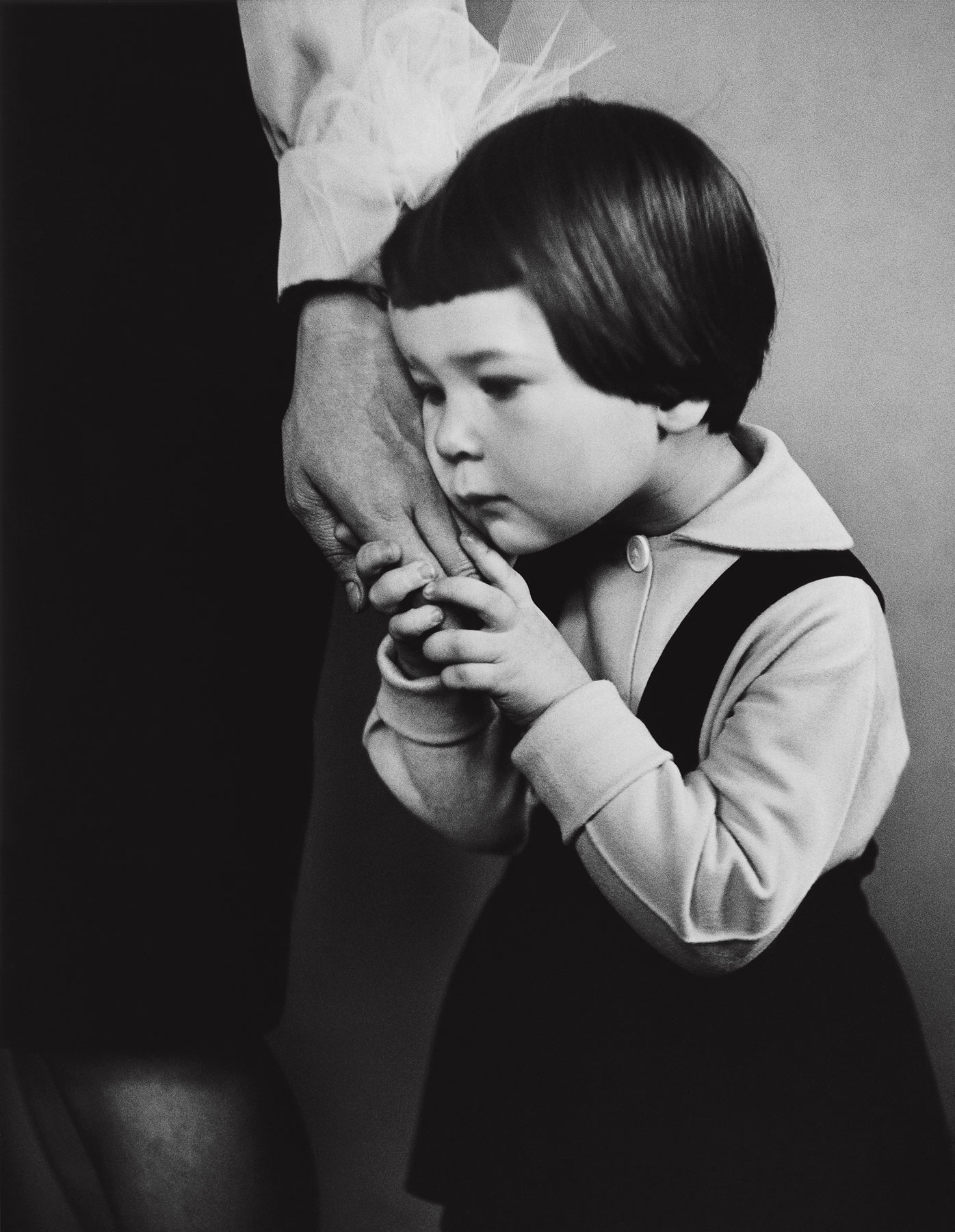

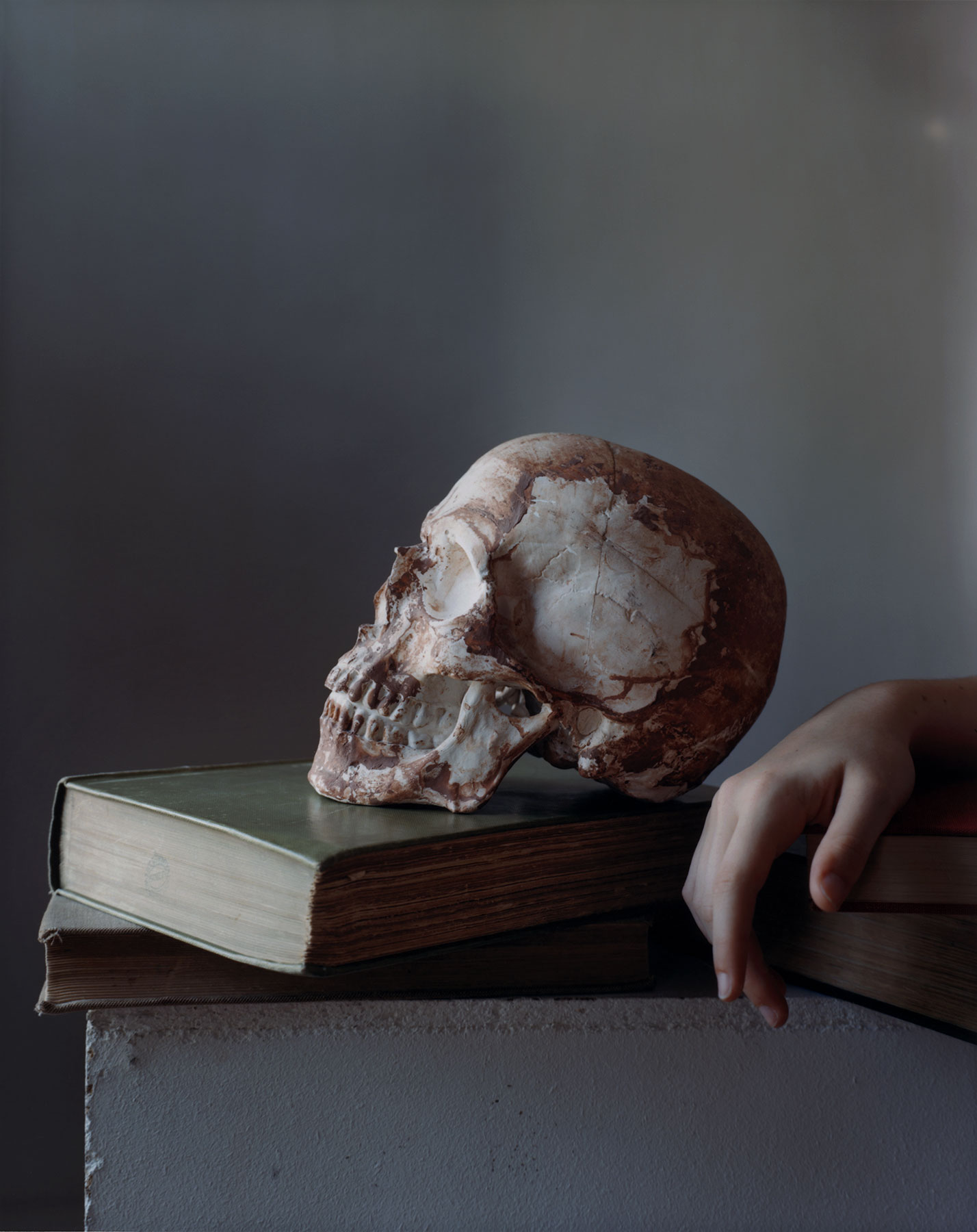

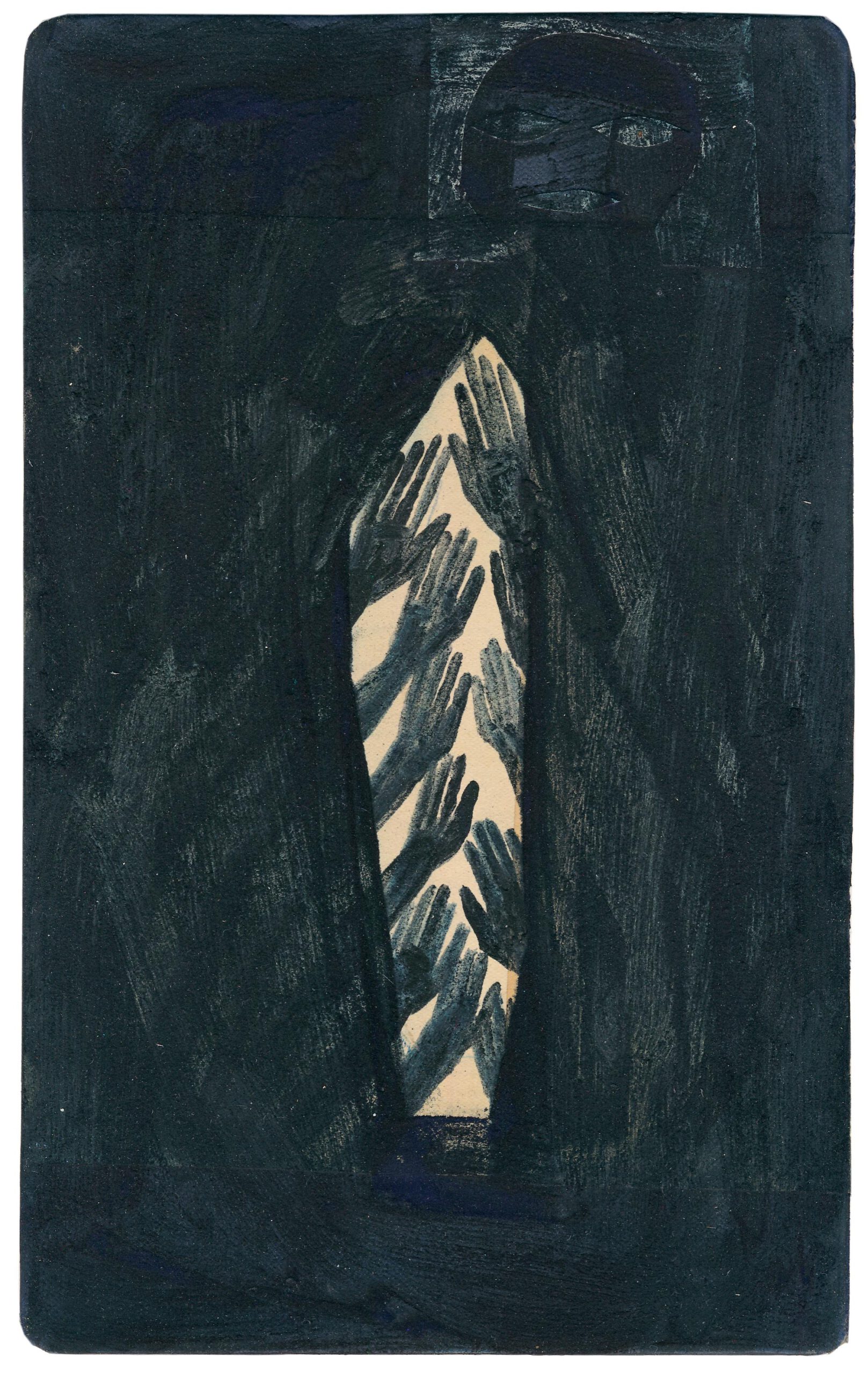

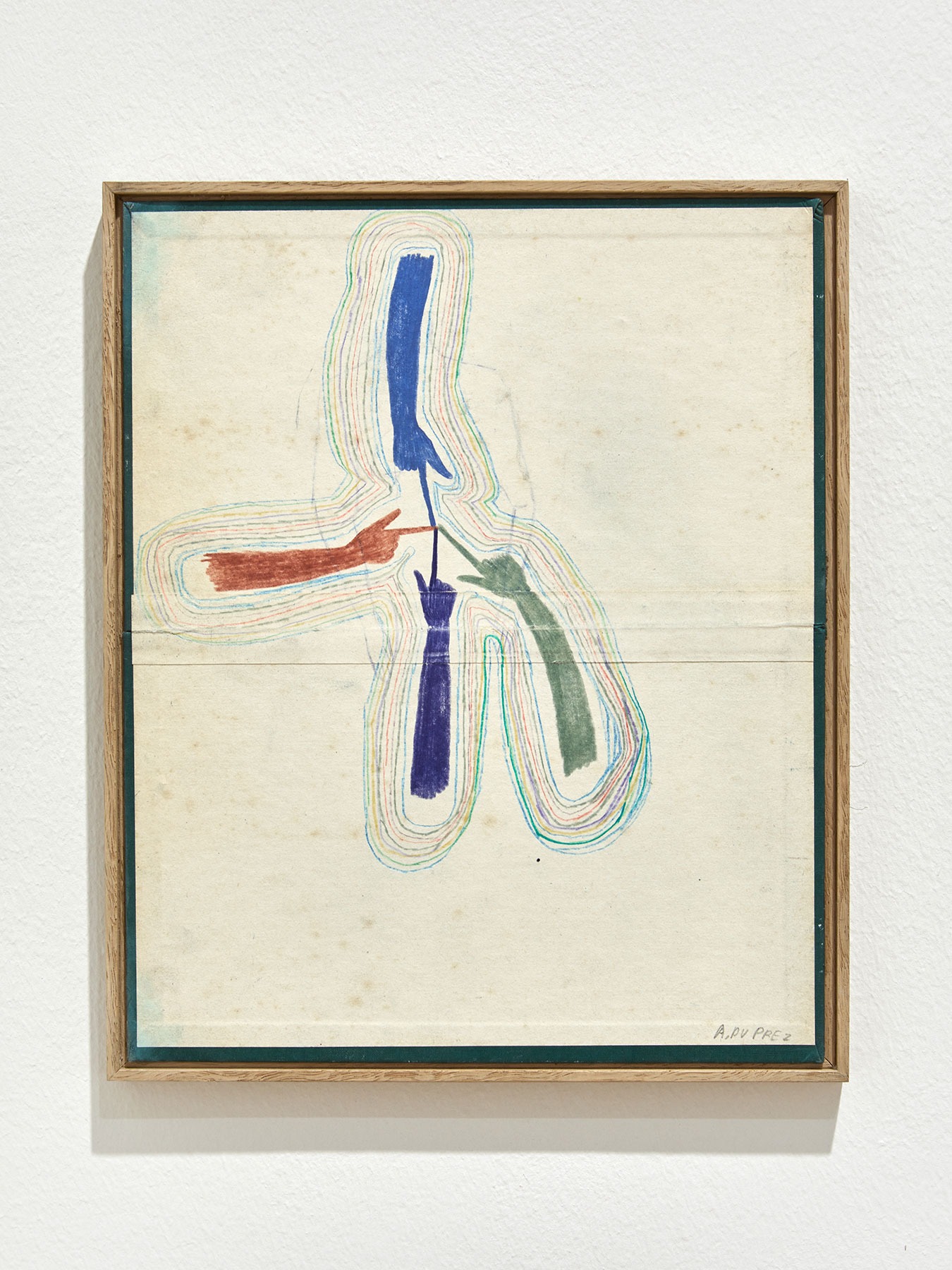

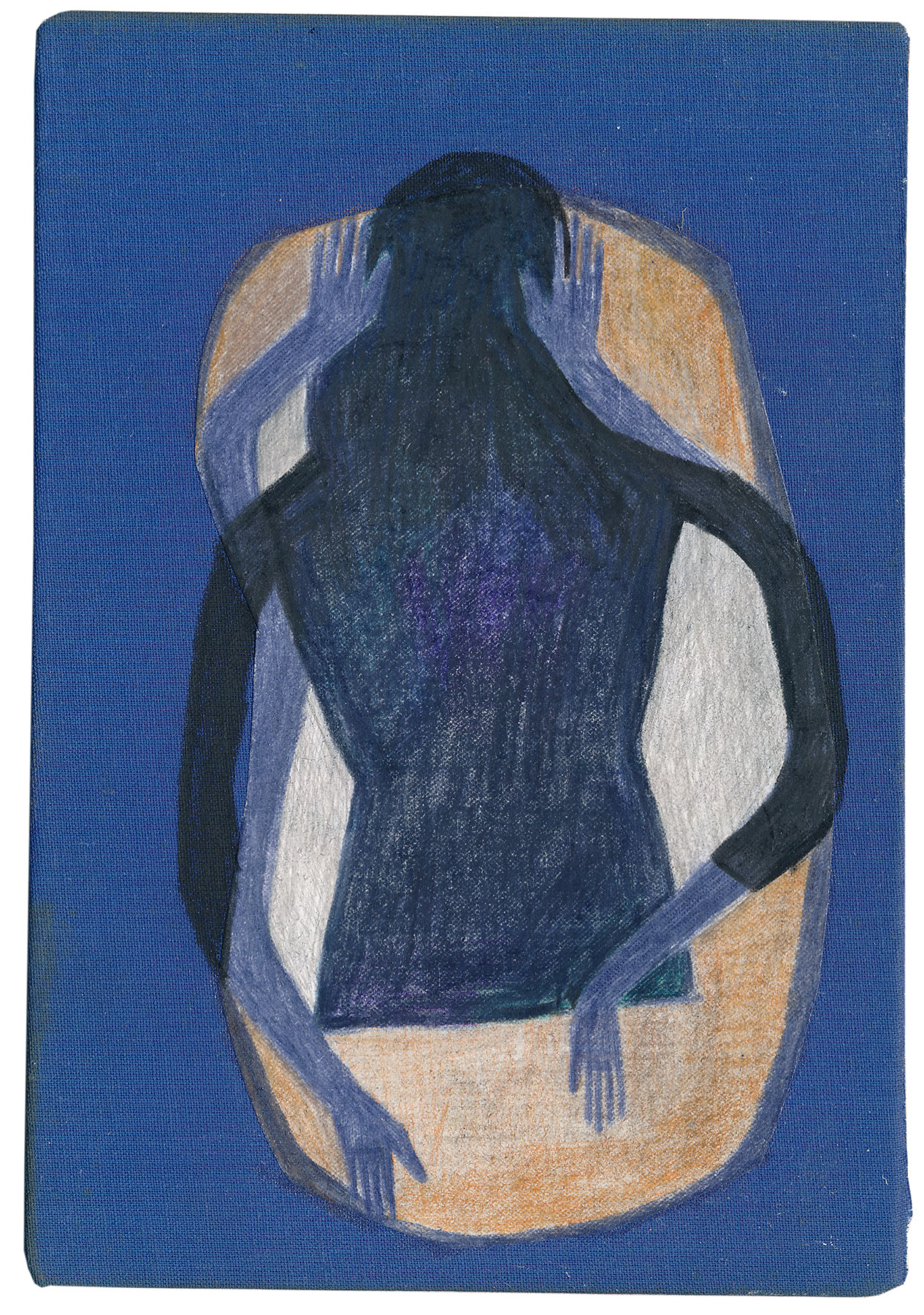

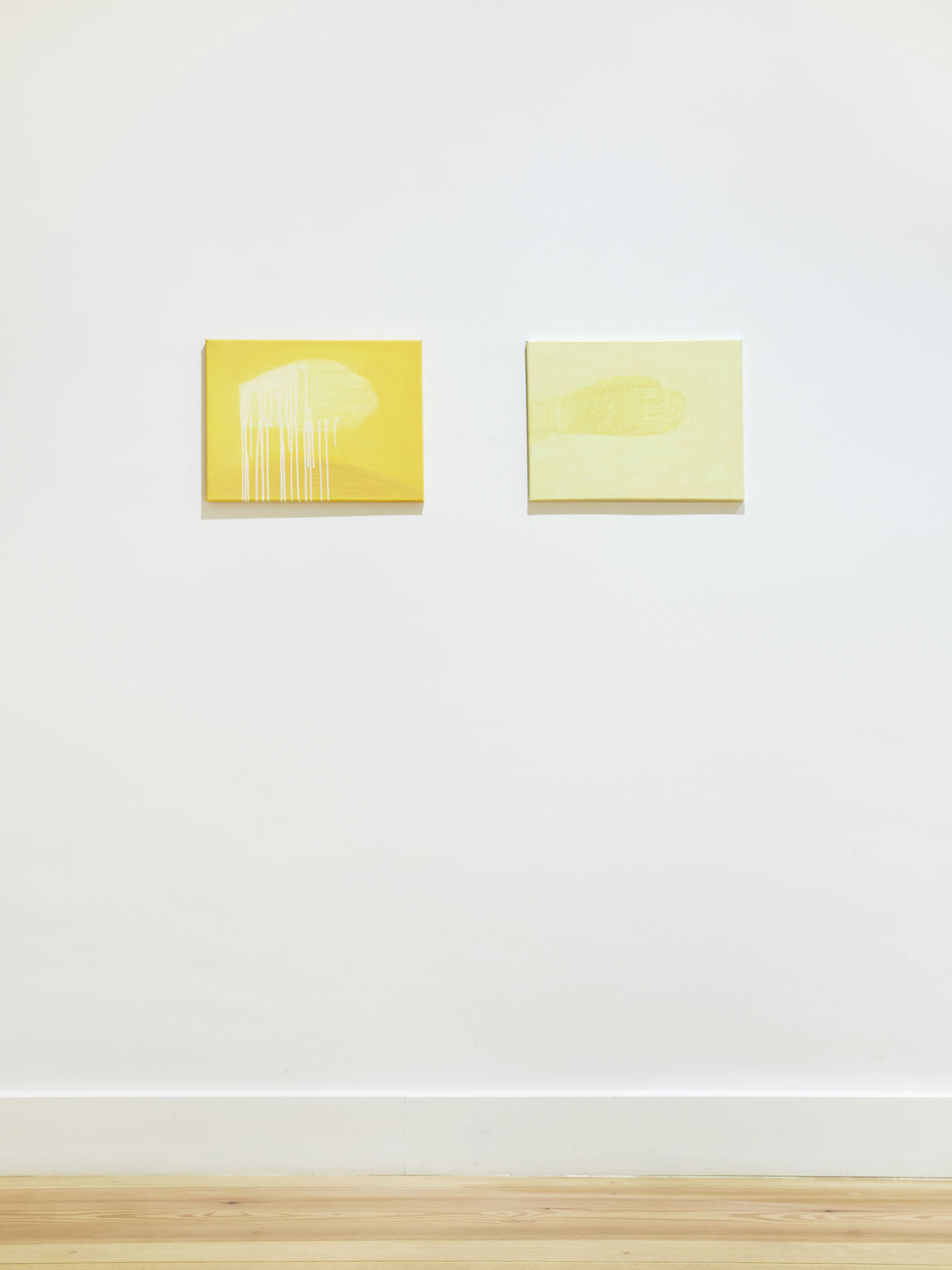

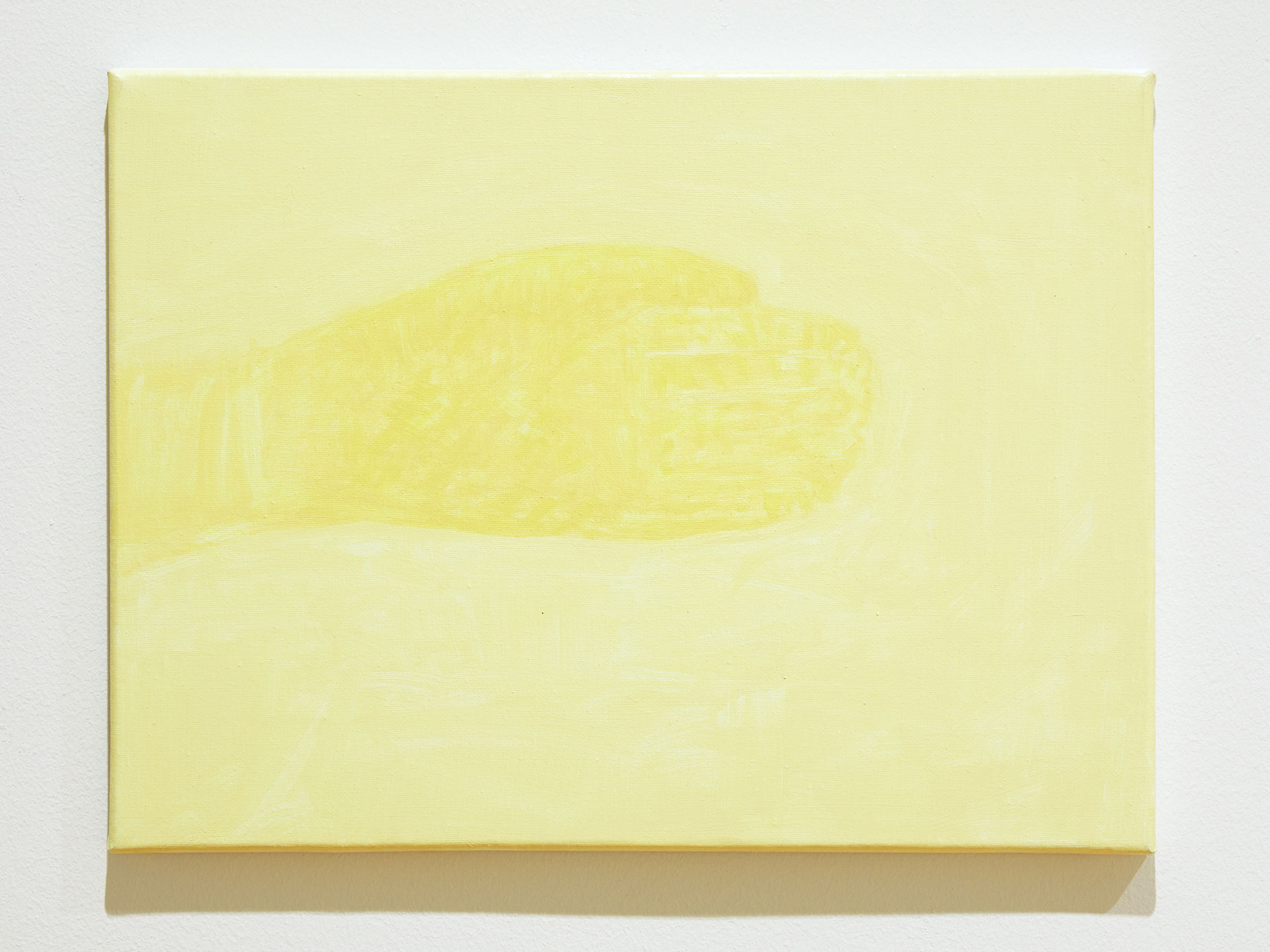

Die Ausstellung steckt dem Thema einen präzisen Rahmen. Es werden nur Werke gezeigt, in denen die Hand das zentrale Motiv ist. Wir wählten Darstellungen aus Fotografie, Malerei, Zeichnung und Skulptur, die verschiedene Wirkungs- und Handlungsweisen beleuchten. Die Kugel, die durch die sie haltende Hand zum Kunstwerk wird (Daniel Gustav Cramer), Aufmerksamkeit fordernde Hände beim Dirigieren (Ruth Bernhard), die innige Verbindung zwischen der Hand der Mutter und des Kinds (Antanas Sutkus), die Hand und ihre Nähe zum Tod (Olivier Richon), sich im Kampf verschlingende Hände (Sandy Volz), die Hand als spielerisches Dekor (Alexandra Duprez), Hände in Trauer und Schmerz (Sim Cha Chi) oder als Träger von Sensualität und Geheimnis (Rafael Cidoncha).

Hands and What They Mean

In light of the discussion about AI and the fear that it might assume control over humans, it is worthwhile to consider humans’ other cognitive capacities. It is easily overlooked that our brain – with which we compete with AI – is not the only important element of the human body. The hand precedes thinking. Only thanks to the hand is the human being a homo faber – a technical creature (Hans Blumenberg).

From the beginning, humans are dependent on their hands. We can only eat on our own if we can grasp, and experience space only by touching. We are dependent on touch, and we want to touch. We need the sensual experiences we have with their help as we need air to breathe. Should AI ever take over thinking, we will still survive with the aid of our hands. The computer may comprehend the function of the brain, but the hand is outside of its scope. “While the giants of the tech industry dream of conquering the universe, something as elemental as a human hand cannot be represented by this artificial intelligence?” (Hito Steyerl)

AI image generators do indeed have a problem with human hands. Even if one day they will get so far that they can represent it correctly, can they replace the hand? It doesn’t seem to be possible. Because unlike the static brain, hands move, and even if their pure functions may be realized technically, the non-functional aspect of hands is reserved to humans: the healing or helping hand, the extended, rescuing hand. The hand can create trust and security – to this day, contracts are sealed with a handshake. But it can also be violent and kill. Over the course of a life, a hand develops and changes and stands for a life lived – the past and the future can be read in it.

The exhibition sets a very precise frame for the subject. It contains only works where the hand is the central motif. We chose representations from the fields of photograph, painting, drawing, and sculpture that illuminate different modes of operation and action. The sphere that becomes a work of art through the hand holding it (Daniel Gustav Cramer), the hands demanding attention when conducting (Ruth Bernhard), the intimate connection between the mother’s hand and that of her child (Antanas Sutkus), the hand and its proximity to death (Olivier Richon), hands intertwined in struggle (Sandy Volz), the hand as playful decor (Alexandra Duprez), hands in mourning and pain (Sim Cha Chi), or as the carriers of sensuality and mystery (Rafael Cidoncha).

Installation views: Sandy Volz